Following our second interview Kellan snuck in 5 Questions for Paul Mison before I managed to tap Jim’s suggestion of Gustavo.

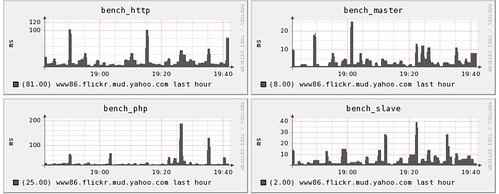

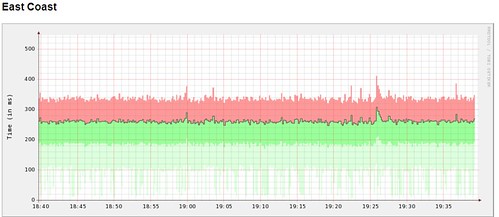

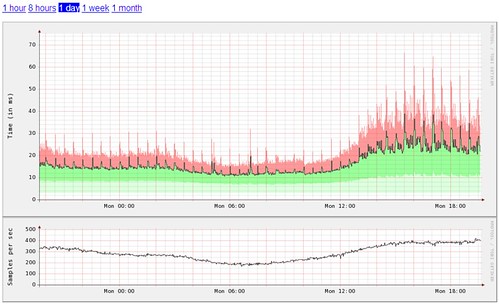

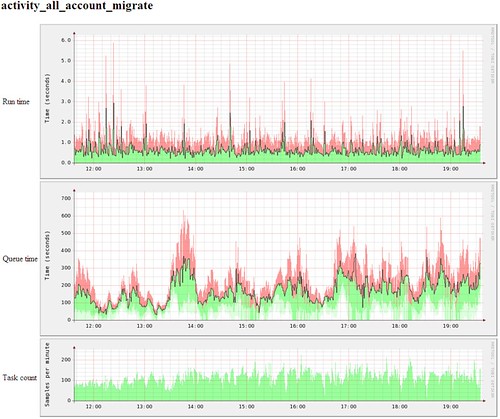

I think Drift Words sums Gustavo up nicely with “Although he’s far too clever, he makes up for it by using his polymath powers for good.” … and charts and stunning graphs. It’s always a pleasure to see what Gustavo comes up with.

And on that note …

1. What are you currently building that integrates with Flickr, or a past favorite that you think is cool, neat, popular and worth telling folks about? Or both.

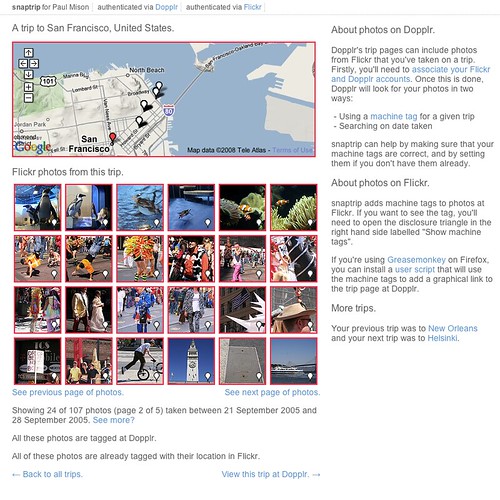

Gustavo: First of all I must say: I’m not really a flickr tool developer. The only real tools I created are the quite minimalistic FlickRandom and Contact Crossing (very kindly hosted by Jim Bumgardner). Rather, I use flickr’s API to mine flickr’s database for interesting information, usually leading to some visualizations or at the very least a bunch of graphs.

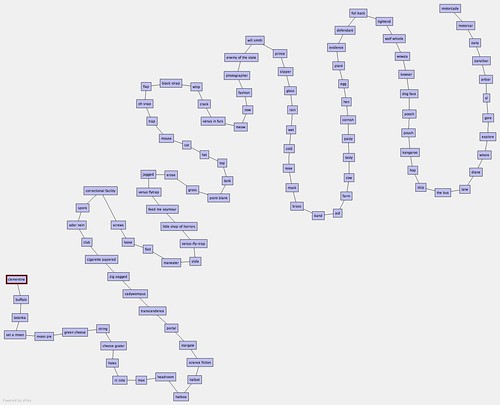

One such visualization led to a browser for exploring related groups. Not a full-fledged tool since it explores static and outdated data.

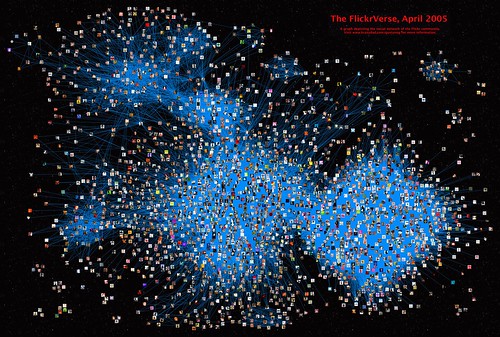

In other words, what I do with flickr’s API is not tool development but analyses, trying to figure out the structure and dynamics of flickr’s social network, group content and participation, etc. The most recent analysis I performed attempted to understand how exposure to photo content flows through the contact network. Starting from a basic pattern combining three types of network relations, I quantified the importance of a user’s social network in determining his or her exposure to content of interest.

2. What are the best tricks or tips you’ve learned working with the Flickr API?

Gustavo: Cache, cache, cache. Depending on what you want to do, you might find yourself retrieving certain bits repeatedly, and you’ll definitely want to build a good local cache. Be careful though, as it’s all too easy to underestimate the size and complexity of the data. Your cache might unexpectedly morph from a speed asset to a sluggish monster.

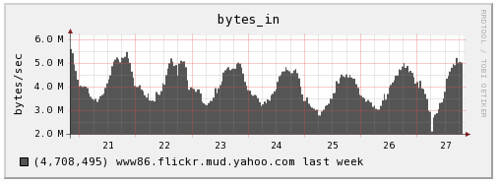

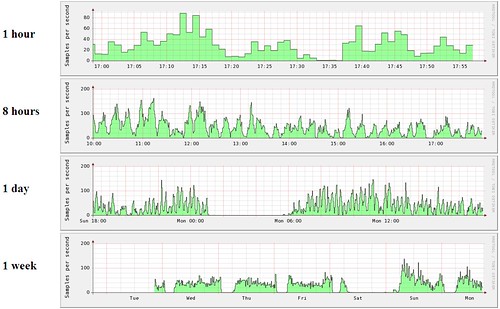

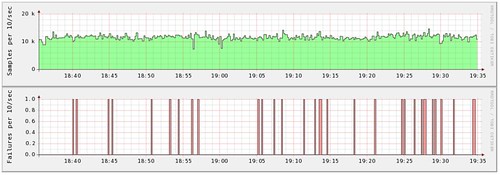

Another potential problem from underestimating the size and complexity of the data is that you might suddenly discover that your code issued many more API calls than you expected. Remember to play nice, and keep an eye on your API key usage graphs.

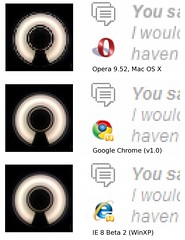

Expect unexpected responses: It’s always good to make the code smart enough to realize the server’s response is not exactly what was expected, be it in completeness, format, special characters in free text, etc.

Finally, still on the theme of unexpected responses: Grow a thick skin, as there will always be someone who will misinterpret your motives for developing a tool that “uses” their information.

3. As a Flickr developer what would you like to see Flickr do more of and why?

Gustavo: Let me suggest two: one very simple, the other very complex.

The simple one is a “no special perms” authentication level. For some purposes, as a developer I’d like to have the user authenticate for the sole purpose of knowing who they are – I might want to give certain results for their eyes only, or someone else might want to allow certain actions to happen just once per user, etc. At the moment, the minimal level of authentication requires that the user entrust the developer with access to private data. Many users will rightfully decline giving such access, and as a developer I’d rather not have to even request and disclaim, when I don’t need it.

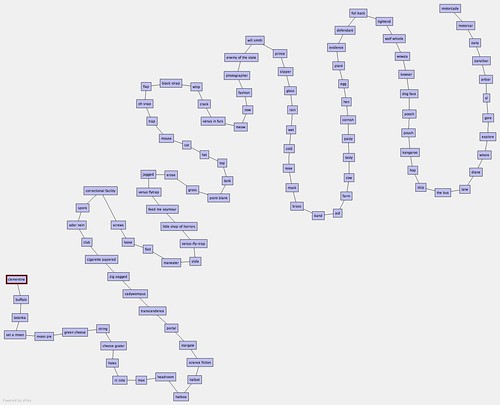

The more complex one requires a bit of background. Almost four years ago, there were various discussion threads on the topic of finding interesting content. Back then I took a stab at using network information to discover interesting photos – first looking for people who post similar stuff, then looking for people who share faved photos (which striatic called neighbors) and finally, actual photo suggestions.

As an aside, the algorithm worked quite well even for people with a hundred or so favorites (I had just 21 faves!); people today have many thousand favorites – a very rich data set to start from. I went on to produce suggestion lists for many people, but that was always me, manually running scripts. Since then, other developers created interesting tools for content-driven content discovery, including Flickr Cross-Recommendations, inSuggest and flexplore.

The reason I never tried to create a stand-alone tool for this is that I quickly realized that to make it work reasonably fast, I essentially needed to replicate flickr’s database. If you take all my favorites, then list all the people that faved those photos, and finally enumerate all their favorites… and you then repeat this exercise for whoever requests it, you either need to use many thousand API calls per visitor (and wait!), or you need to create a huge cache, covering unpredictably disparate segments of flickr’s database. A massive cache that would grow stale very quickly unless people used the tool continuously. If you try to include extra information into the scoring scheme (say tags, color data, group membership…) the network use and storage requirements grow even worse. In other words, this project appears to be completely unsuitable for a developer without direct access to flickr’s database… and flickr’s content suggestion system (Explore) doesn’t provide any personalization tools: we all see the same.

The only effective solution I can suggest (beyond flickr developing a personalized Explore, or flickr sandboxing third party developers) is the creation of high level API calls, embodying some method of complex querying into the database. For example: A higher level API call could accept a list of users as query, and return a list of photos sorted by the number of people (from the query list) who faved them. With the current API, one has to retrieve the full favorites list for each person, collate the results, and discard the vast majority of the information that was transferred. A higher level API method could make such intermediary results invisible and save much bandwidth, latency and data replication.

Hey, you asked. ;)

4. What excites you about Flick and hacking? What do you think you’ll build next or would like someone else to build so you don’t have to?

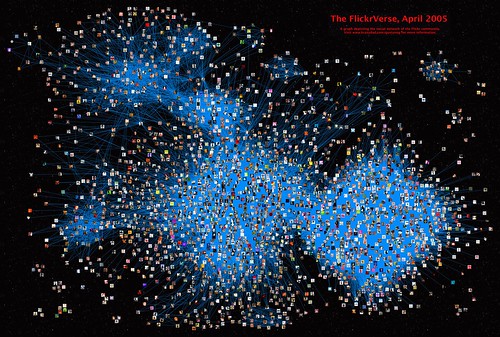

Gustavo: There’s a number of things that attract me to flickr hacking. There’s of course the vast and ever-growing amounts of data, and the fact that it’s not “more of the same”: The diversity of data types (photos, users, metadata, groups, etc) and relations make this complex system fascinating to study. There is also the human side: People really care about their stuff. People get excited, for example, when they recognize their user icon in a visualization of the social network, and immediately want to explore around. Last but not least, I really appreciate the openness of the flickr API. I’m amazed that such wealth of information is shared so freely!

As for “what next”, I have a couple of ideas. I’ll only hint that the word association analysis was a fun first step. :)

5. Besides your own, what Flickr projects and hacks do you use on a regular basis? Who should we interview next?

Gustavo: dopiaza as Utata‘s architect.

Dan: Thank you, Gustavo. Next up (unless Kellan gets in first!) dopiaza.

Images from GustavoG,

striatic and malanalars.