![]() Introducing guest blogger, Ari Fuchs. He is a Lead API Engineer and Developer Evangelist at Aviary. He has spent the last 3 years building out Aviary’s internal and external facing APIs, and is now working with partners to bring Aviary’s tools to the masses. He also did a lot of work to bring the Aviary editor to Flickr. Follow him on Twitter and send him a nice message to make him feel better about his stolen bike. Now, on to his post…

Introducing guest blogger, Ari Fuchs. He is a Lead API Engineer and Developer Evangelist at Aviary. He has spent the last 3 years building out Aviary’s internal and external facing APIs, and is now working with partners to bring Aviary’s tools to the masses. He also did a lot of work to bring the Aviary editor to Flickr. Follow him on Twitter and send him a nice message to make him feel better about his stolen bike. Now, on to his post…

At Aviary, we’ve been passionate about photos since day one. It’s been five years since we released our first creative tool, Phoenix, a powerful, free Flash-based photo editor. Phoenix offered functionality on par with Adobe Photoshop 5 and a price point that opened its usage to anyone with an internet connection. As amateur photographers worldwide began trying their hand at editing, we watched our product join the ranks of a small number of companies working to democratize the process of photo editing for the first time.

Around two years ago we began rethinking the future of our tool set. While our original tools offered incredible functionality, they did have a learning curve which meant that the average person couldn’t just sit down and begin editing without investing time to become familiar with the tools. We wanted to build a powerful editor that anyone could use.

Because we were rebuilding the editor from the ground up, we took the opportunity to switch from a Flash based solution to one built using HTML5 technologies. We saw this as an opportunity to build on a growing standard, and to support the most platforms.

In fall of 2010 we released our HTML5 photo editor which has evolved into the product we’re proud to share with you today.

Widget Encapsulation

During our initial foray into the online editor space, we took a straightforward approach by having API users launch our editor in a new page or window. This simplified integrations and allowed us to own the editing experience.

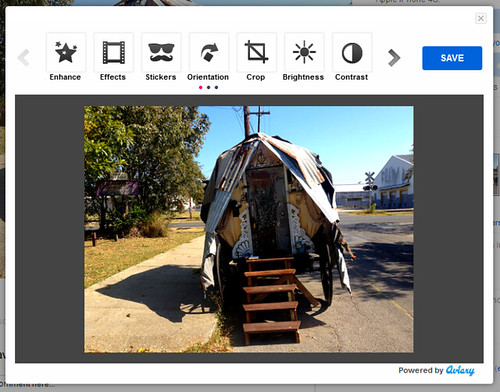

When we rebuilt our editor in JavaScript, we took the opportunity to re-architect our API as well. Our first big change was making the editor embeddable. This meant that third party developers could load the editor on their own sites, maintaining user engagement while controlling their experience. We built out customization options that allowed the site owner to decide which tools appeared in the editor. A real estate site, for example, might not want its users adding mustache stickers to appliances in photos.

Our editor, unlike many rich HTML widgets, does not require an iframe and is truly embedded into a hosting webpage. This posed many challenges during development, but the result is a more seamless, lightweight integration.

Constructor API

When we rebuilt our API, we took a leap by assuming that web developers integrating our editor would have experience with other JavaScript libraries and plugins. We built our API to use a Constructor method that accepts a configuration object to allow for the aforementioned tool customization. The configuration object is also used to configure callbacks, image URLs, language settings, etc., and allows us to continue building out our API without losing backwards compatibility.

Simplifying the Save Process

Saving image data is always a challenge in the browser, and can require various cross-browser workarounds. An obvious method would be to initiate a form post to the server and include the base64 image data in a hidden field. This breaks in Safari, where form fields have an undocumented value length limit. We worked around this by switching to an ajax post with the appropriate CORS headers to get around cross domain issues. In browsers that don’t support CORS, we fall back to the form post method.

To hide this complexity from the developer, we’ve abstracted the save process completely. When a user saves an edited image, we temporarily save the image data to our own servers and return a public URL so the host application can download the image to their own.

High Resolution Photos

One of the coolest features of our editor is the high resolution image support — that being said, it certainly has a number of challenges. There’s the practical issue of limited real estate in the browser (keep an eye out for updates addressing this in the near future), as well as performance issues that are harder to quantify. Even in Flash based tools, the size of the image you can edit in the browser is limited by a number of gating factors: hardware specs, number of running processes, etc. To get around these client limitations, we’ve set a configurable maxSize on the editor and added a configuration field for an original-resolution version of the image to be edited: hiresUrl.

When a hiresUrl is supplied, every user edit action is logged. On save, the aptly named “actionlist” is sent to our server along with the hiresUrl. When it hits our render farm, the actionlist is replayed on the high resolution image, and the final results are returned to the host site via a new hiresUrl.

{

"metadata": {

"imageorigsize": [

800,

530

]

},

"actionlist": [

{

"action": "setfeathereditsize",

"width": 800,

"height": 530

},

{

"action": "flatten"

},

{

"action": "redeye",

"radius": 5,

"pointlist": [

[545, 183], [546,183], [547,182], [548,181], [548,179], [548,177], [547,177], [545,177], [544,177], [543,177], [542,177], [541,179], [541,181], [541,183], [542,184]

]

},

{

"action": "redeye",

"radius": 5,

"pointlist": [

[481, 191], [481,193], [481,195], [482,196], [483,197], [484,198], [485,197], [485,196], [485,193], [485,190], [485,189], [485,188], [484,188], [482,188], [480,189], [480,190], [480, 191]

]

},

{

"action": "sharpen",

"value": 21.69312,

"flatten": true

}

]

}

As a side note, we maintain feature parity across all of our platforms (mobile included) by prototyping new tools and filters in the JavaScript first, and then porting them to C for our render farm and Android, and then to Objective-C for our iPhone SDK. By maintaining feature parity and synchronizing output across platforms, we’re able to ensure that users get the edits they expect on their high resolution photos, and we keep the door open for future server-side support for our mobile SDKs where the original photo might not be stored on the device.

Tools and Libraries

We use some pretty awesome tools to help us maintain cross-browser compatibility.

LESS CSS

We moved a lot of the cross-browser concerns to build-time with LESS and a library of mix-ins inspired initially by Twitter Bootstrap, though the final result is wholly our own. LESS’s color math and variables let us achieve a textured and rounded look and feel while minimizing complexity during development.

/* LESS */

.avpw_inset_button_group {

#gradient > .vertical(lighten(@conveyorBelt, 4%), darken(@conveyorBelt, 1%));

.box-shadow(inset 0 0 4px darken(@conveyorBelt, 20%));

.border-radius(8px);

}

/* EXPANDED */

.avpw_inset_button_group {

background-color: #2a2a2a;

background-repeat: repeat-x;

background-image: -khtml-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom, from(#383838), to(#2a2a2a));

background-image: -moz-linear-gradient(top, #383838, #2a2a2a);

background-image: -ms-linear-gradient(top, #383838, #2a2a2a);

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom, color-stop(0%, #383838), color-stop(100%, #2a2a2a));

background-image: -webkit-linear-gradient(top, #383838, #2a2a2a);

background-image: -o-linear-gradient(top, #383838, #2a2a2a);

background-image: linear-gradient(top, #383838, #2a2a2a);

filter: progid:DXImageTransform.Microsoft.gradient(startColorstr='#383838', endColorstr='#2a2a2a', GradientType=0);

-webkit-box-shadow: inset 0 0 4px #000000;

-moz-box-shadow: inset 0 0 4px #000000;

box-shadow: inset 0 0 4px #000000;

-webkit-border-radius: 8px;

-moz-border-radius: 8px;

border-radius: 8px;

}

CSS3

With CSS3, we’ve just about managed a complete break from the DHTML effects of the past. The new UI uses CSS3 transitions and transforms wherever possible to remain future-proof.

Flash

Yes, our editor does indeed have a Flash fallback for browsers that lack certain HTML5 features (namely canvas). We initially built the editor as a move away from Flash, but because of the legacy IE7 and IE8 userbases on our larger partner sites, we had to go back and rebuild certain components in Flash to support those browsers.

We’ve architected the editor so that Flash is only being used where necessary. Some tools, such as draw, have been completely rebuilt in Flash; for others, like effects, the bitmap data is being exported and manipulated in JavaScript (using a reverse implementation of pibeca). This allows for code reuse, and enables us to build new features faster with more backwards compatibility.

Future

While the feedback for our editor has been overwhelmingly fantastic, we’re continuing to work hard building out new tools and features, and performance enhancements to our existing set.