When you have thousands of photos, it can be hard to find the photo you’re looking for. Want to search for that Christmas cat you saw at last year’s party? And what if that party wasn’t on Christmas day, but sometime the week before? To help improve the search ranking and relevance of national, personal, and religious holiday photos, we first have to see when the photos were taken; when, for example, is the Christmas season?

Understanding what people are looking for when they search for their own photos is an important part of improving Flickr. Earlier this year, we began a study (which will be published at CHI 2016 under the same name as this post) by trying to understand how people searched for their personal photos. We showed a group of 74 participants roughly 20 of their own photos on Flickr, and asked them what they’d put into the Flickr search box to find those photos. We did this a total of 1492 times.

It turns out 12% of the time people used a temporal term in searches for their own photos, meaning a word connected to time in some way. These might include a year (2015), a month (January), a season (winter), or a holiday or special event (Thanksgiving, Eid al-Fitr, Easter, Passover, Burning Man). Often, however, the date and time on the photograph didn’t match the search term: the year would be wrong, or people would search for a photograph of snow the weekend after Thanksgiving with the word “winter,” despite the fact that winter doesn’t officially begin until December 21st in the U.S. So we wanted to understand that situation: how often does fall feel like winter?

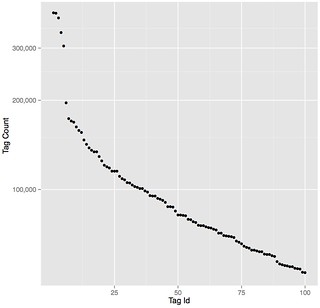

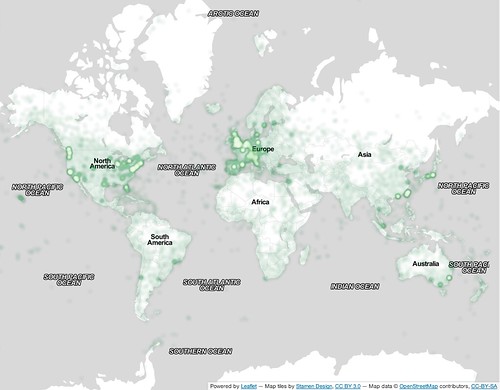

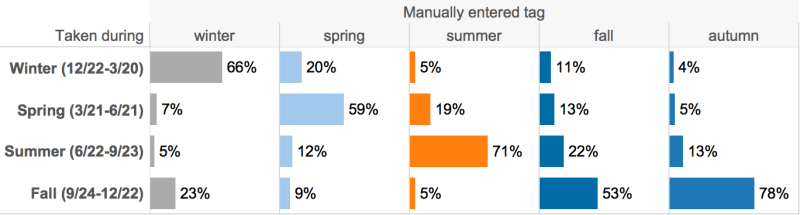

To answer this, we mapped 78.8 million Flickr photos tagged with a season name to the date the photo was actually taken.

As you’d expect, most of the photographs tagged with a season are taken during that season: 66% of photos tagged “winter” were taken between December 22 and March 20. About 9% of search words are off by two seasons: photos tagged “summer” that were taken between December 21st and March 20th, for example. We expect this may reflect antipodean seasons: while most Flickr users are in the Northern Hemisphere, it doesn’t seem unreasonable that 5% of “summer” photographs might have been taken in the Southern Hemisphere. More interesting, we think, are the off-by-one cases, like fall photographs labeled as “winter,” where we believe that the photo represents the experience of winter, regardless of the objective reality of the calendar. For example, if it snows the day after Thanksgiving, it definitely feels like winter.

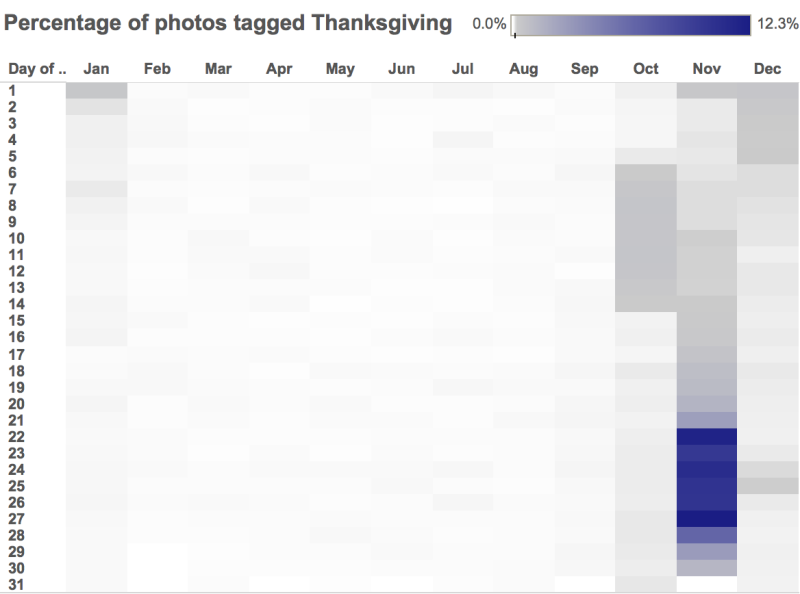

On the topic of Thanksgiving, let’s look at photographs tagged “thanksgiving.”

The six days between November 22nd and 27th—the darkest blue area—cover 65% of the photos. Expanding that range to November 15–30th covers 83%. Expanding to all of November covers 85%, and including October (and thus Canadian Thanksgiving, in gray in early October) brings the total to 90%. But that means that 10% of all photos tagged “thanksgiving” are outside of this range. Every date in that image represents a total of a minimum of 40 photographs taken on that day between 2003 and 2014 inclusive, uploaded to Flickr and tagged “thanksgiving” with the only white spaces being days that don’t exist, like February 30th or April 31st. Manual verification of some of the public photos tagged “thanksgiving” on arbitrarily chosen dates finds these photographs tagged “thanksgiving” included pumpkins or turkeys, autumnal leaves or cornucopias—all images culturally associated with the holiday.

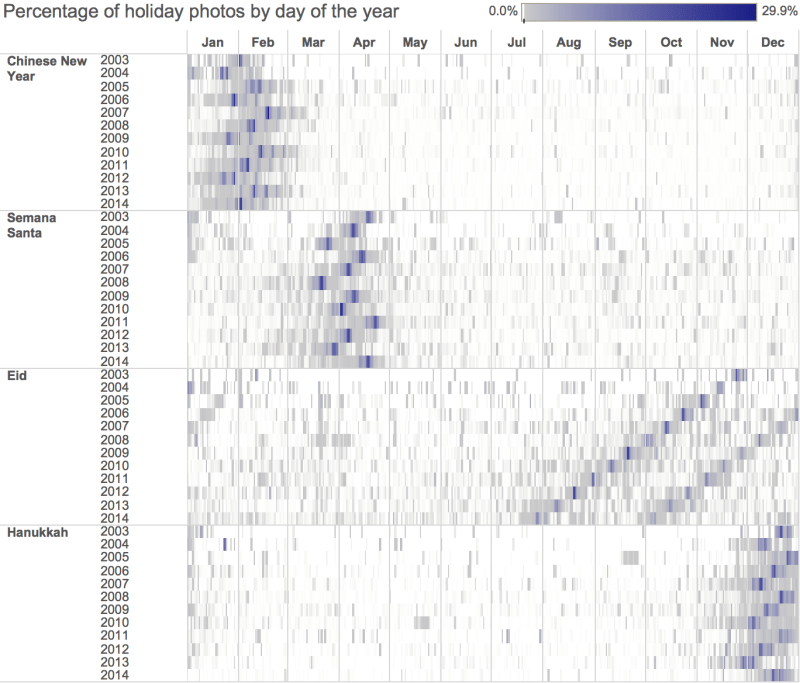

Not all temporal search terms are quite so complicated; some holidays are celebrated and photographed on a single day each year, like Canada Day (July 1st) or Boxing Day (December 26th). While these holidays can be easily translated to date queries, other holidays have more complicated temporal patterns. Have a look at these lunar holidays.

There are some events that occur on a lunar calendar like Chinese New Year, Easter, Eid (both al-Fitr and al-Adha), and Hanukkah. These events move around in a regular, algorithmically determinable, but sometimes complicated, way. Most of these holidays tend to oscillate as a leap calculation is added periodically to synchronize the lunar timing to the solar calendar. However Eids, on the Hijri calendar, have no such leap correction, and we see photos tagged “Eid” edge forward year after year.

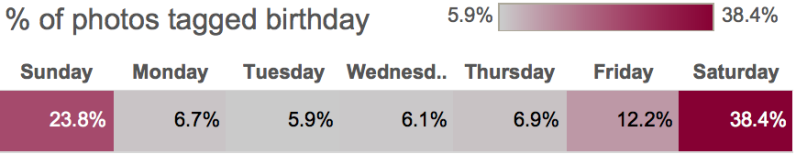

Some holidays and events, like birthdays, happen on every day of the week. But they’re often celebrated, and thus photographed, on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday:

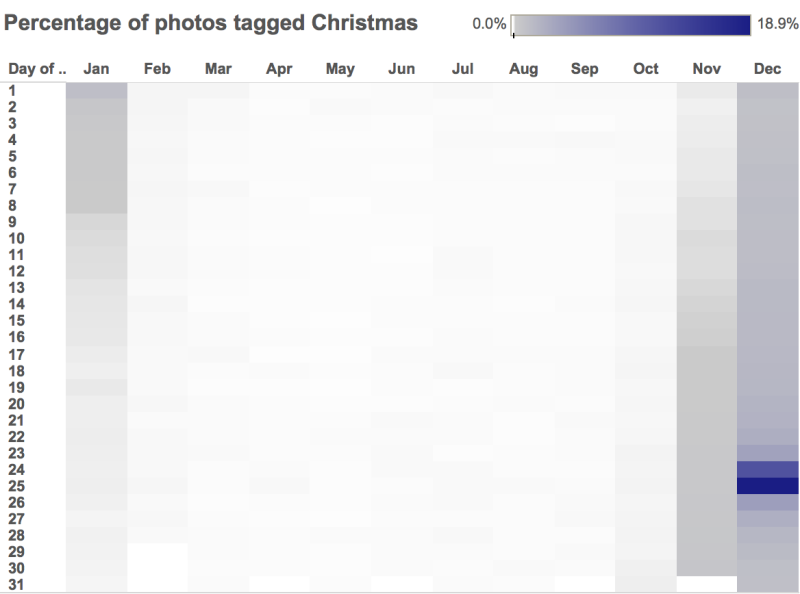

So to get back to our original question: when are photos tagged “Christmas” actually taken?

As you can see, more photos tagged “Christmas” are taken on December 25th than on any other day (19%). Christmas Eve is a close second, at 12%. If you look at other languages, this difference practically goes away: 9.2% of photos tagged “Noel” are taken on Christmas Eve, and 9.6% are taken on Christmas; “navidad” photos are 11.3% on Christmas Eve and 12.0% on Christmas. But Christmas photos are taken throughout December. We can now set a threshold for a definition of Christmas: say if at least 1% of the photos tagged “Christmas” were taken on that day, we’d rank it more relevant. That means that every day from December 1st to January 1st hits that definition, with December 2nd barely scraping in. That makes…32 days of Christmas!

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays—for all the holidays you celebrate and photograph.

PS: Flickr is hiring! Labs is hiring! Come join us!